South Carolina

Guide to Beachfront

Property

Insight for Informed Decisions

Financial assistance provided under Cooperative Agreement NA12NOS4190094 by the Coastal

Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended, administered by the Office of Ocean and Coastal

Resource Management, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Table of Contents

Introduction ...........................................................................................1

Common Coastal Hazards .................................................................... 2

Long-Term Chronic Erosion .................................................................................. 2

Storm-Driven Erosion ............................................................................................ 3

Flooding ................................................................................................................... 4

Avoid Purchasing Property Prone to Hazards ........................................... 4

Understand State Laws .......................................................................................... 5

Determine if Erosion is an Issue ........................................................................... 6

Ask a Licensed Real Estate Professional .............................................................. 7

Research Resilience to Large Storms .................................................................. 7

Seek Local Knowledge ........................................................................................... 8

Investigate Insurance Options & Requirements .................................................. 8

Developing on Coastal Property ....................................................... 11

Building on an Undeveloped Beachfront Lot ........................................... 11

Construction Seaward of the Setback Line ........................................................ 11

Construction Seaward of the Baseline ............................................................... 12

Coastal Construction Features ............................................................................ 13

Waste Management .............................................................................................. 13

Upgrading or Adding to Beachfront Homes ............................................ 14

Protecting & Repairing Coastal Property ......................................... 15

Dunes and Dune Walkovers ................................................................................. 15

Relocation .............................................................................................................. 15

Safe Home Program ............................................................................................. 16

Sandbags, Sand Scraping, and Minor Renourishment .................................... 16

Erosion Control Structures ................................................................................. 17

Recovery After a Storm .............................................................................. 17

Repairing and Rebuilding ..................................................................................... 17

Additional Information & Contacts ...................................................20

Contributing Organizations ...............................................................21

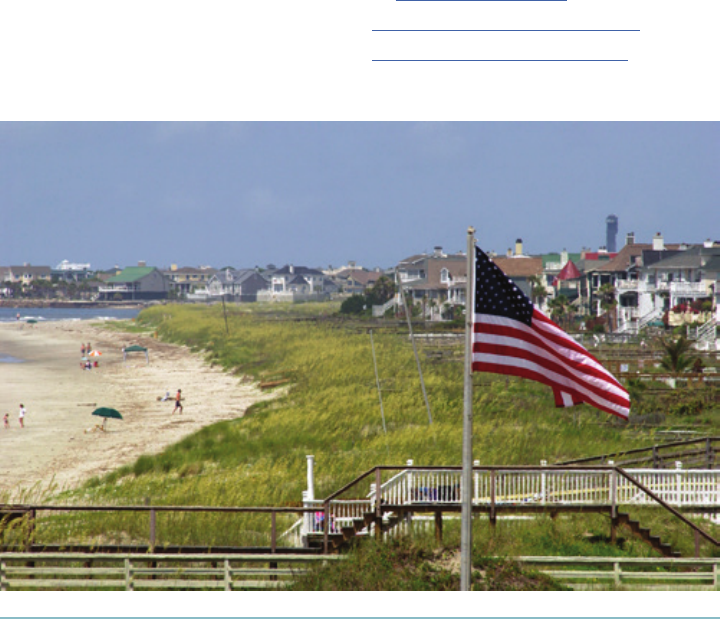

1Introduction

W

ith nearly 200 miles of

oceanfront shoreline, South

Carolina is home to some of the

most spectacular beaches in the

world. The beautiful, dry sand

beaches, rolling dunes, and wildlife

attract vast numbers of tourists,

new residents, and property

investors alike. However, before

purchasing coastal property,

potential buyers should consider

a number of different factors.

Like any other coastal location,

South Carolina oceanfront and

adjacent properties may be

susceptible to an array of natural

hazards. These hazards may

increase ownership costs, including

insurance and hazard mitigation

(e.g. renourishment, building

dunes, moving the structure

more landward, or increasing

the elevation of the structure).

Federal, state, or local laws and

regulations may also affect your

decision to purchase coastal

property. Prospective buyers

and owners should be informed

of the specific laws governing

oceanfront properties and the

types of activities allowed.

This guide is designed to address

questions that arise for individuals

purchasing coastal property. It

provides guidance on topics,

such as what to consider before

buying coastal property, how to

renovate coastal property, and

how to manage the property

should it be damaged by a natural

hazard. Whether considering

an undeveloped lot or one with

an existing structure, there are

critical issues to examine.

Introduction

2 South Carolina Guide to Beachfront Property

T

he South Carolina coastline

is dynamic and constantly

changing due to a common coastal

hazard – beach erosion. Beach

erosion can be a long-term, chronic

condition caused by a variety of

factors, or it may be short-term

as the result of a single or series

of storm events, like hurricanes,

tropical storms, or nor’easters. In

addition to erosion, beachfront

homes may also be threatened

by high wind and flooding from

storm-driven waves or tides.

Long-Term Chronic Erosion

The majority of South Carolina

beaches undergo long-term

chronic erosion, often called

“beach migration,” due to coastal

geological processes. Ocean

currents, prevailing winds,

proximity to inlets, locations of

nearshore sandbars, and other

natural or manmade features

will affect the long-term rate of

erosion along a beach. Chronic

erosion is also exacerbated by

gradually rising sea levels. Sea

level in the Charleston area has

risen more than one foot during

the last century, causing beaches

to migrate landward. Long-term

erosion poses a considerable risk

to beachfront properties, yet it

is often misunderstood. Many

people associate erosion with

short-term storm events and do

not contemplate the effects of

long-term chronic erosion.

Erosion rates are measured by

analyzing historical shoreline

positions and calculating annual

erosion rates based on beach

profile and volumetric data. Erosion

rates can be localized to a specific

area. In fact, it is possible for one

stretch of beach to show no signs of

erosion, while an adjacent stretch

of beach loses a large volume

of sand annually. Beaches along

inlets are often the most unstable

and profoundly affected. Some

“migrating inlets” are constantly

moving in one direction. Others

may expand and contract in

Common Coastal Hazards

3Common Coastal Hazards

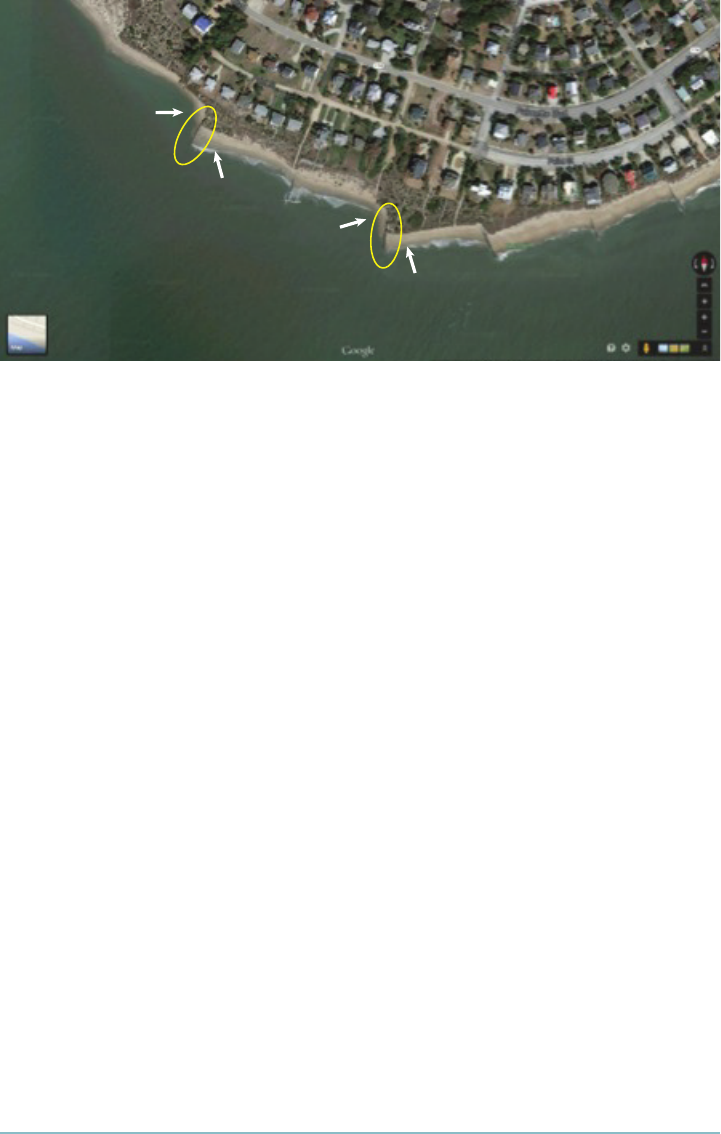

intervals. In addition to natural

causes, chronic erosion can be set

in motion by human activities. For

example, a groin built to stabilize

a portion of the beach can trap

sand on one side but increase

erosion on the other (Figure 1).

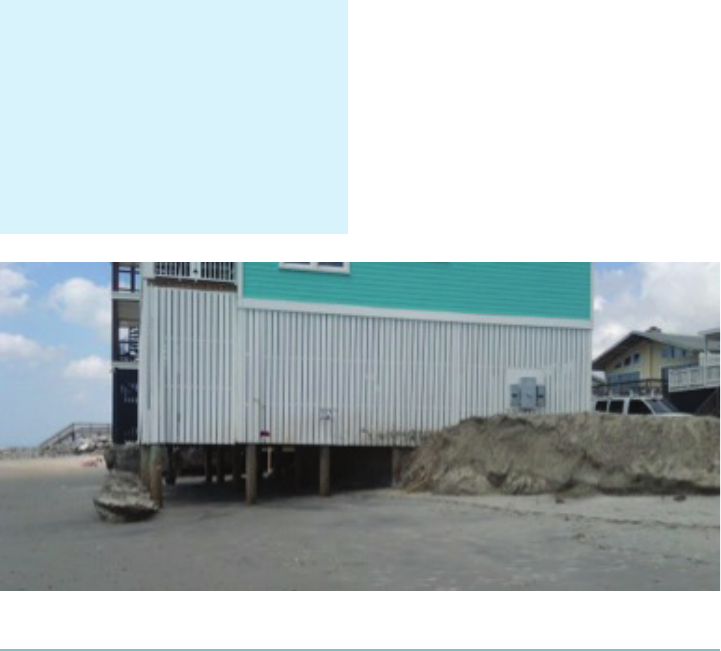

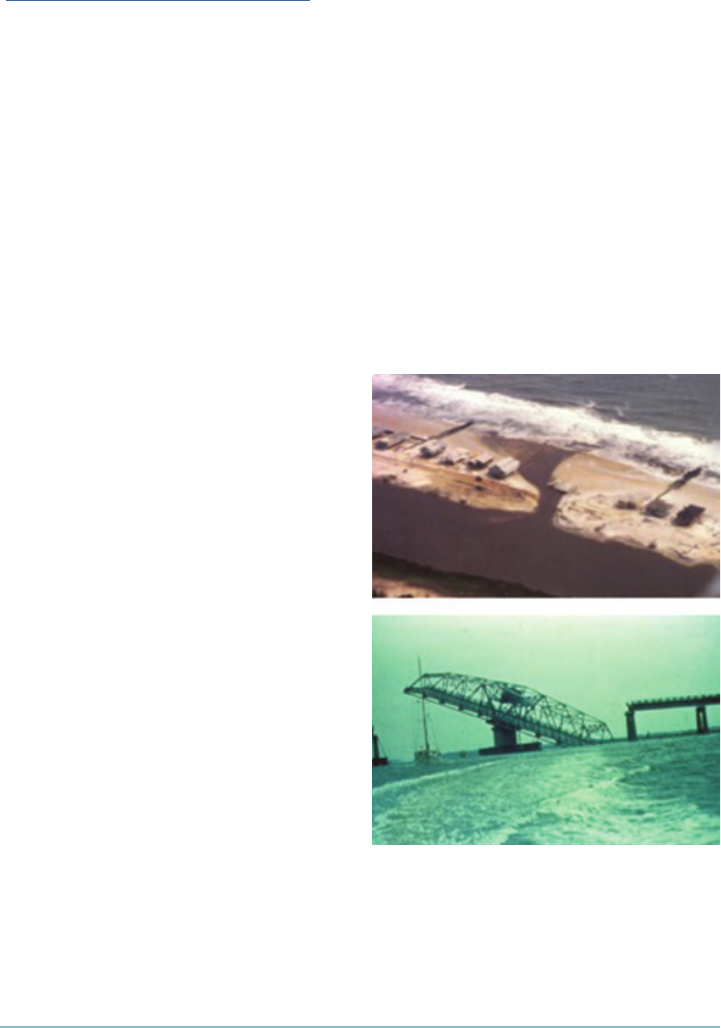

Storm-Driven Erosion

South Carolina’s beaches are

vulnerable to rapid, storm-driven

erosion. Hurricanes, or large

storms like nor’easters, generate

strong waves and currents that

can intensify erosion along

the shoreline. These events,

particularly when coupled with

storm surge, can cause sudden

and widespread changes to the

shoreline and put property in

imminent danger (Figure 2). Even

if a storm does not make landfall,

beaches may still be affected.

Coastal storms also cause seasonal

fluctuations of the shoreline.

Generally, beaches erode more

in the stormy fall and winter

months than in the calm summer

months. Of course, when a beach

is impacted directly by a hurricane,

beachfront erosion can be extensive

and severe. Inlets are also affected

by seasonal storms and can change

configuration rapidly as large

volumes of water and sand flow

through them. In severe storms, it

is even possible for new inlets to

form and existing inlets to close.

Accretion

Erosion

Accretion

Erosion

Figure 1. A groin (yellow circle) can trap sand on one side but increase erosion on the other, as seen in this

example of Edisto Island (Google Map 2014).

4 South Carolina Guide to Beachfront Property

Flooding

Flooding is the most common

disaster in the United States,

and can occur as a result of

storm surge, heavy rain events,

and/or anomalous high tides,

commonly known as King Tides.

Coastal flooding is a common

occurrence, as most coastal

properties are in low-lying areas

and are subject to inundation

from saltwater. In addition to

threatening property, flooding may

reduce mobility or prevent safe

evacuation due to road closures.

AVOID PURCHASING

PROPERTY PRONE

TO HAZARDS

Purchasers of coastal property

should always research coastal

hazards, seeking information on

pertinent laws and regulations

from local governments, the South

Carolina Department of Health

and Environmental Control, Office

of Ocean and Coastal Resource

Management (DHEC-OCRM), and

a licensed real estate professional.

Uninformed decisions can lead to

unexpected costs to the property

owner. Potential buyers take on risk

from damage of a highly erosional

beach, which may result in property

damage and may require further

actions to mitigate the hazard.

Similarly, potential buyers take

on risk by purchasing property

in a flood zone, which may result

in flood damage and expensive

insurance costs if the home is not

Figure 2. Erosion at Folly Beach caused by Tropical Storm Irene in 2011 and Alberto in 2012, both storms

passed more than 100 miles offshore. Photo courtesy of DHEC.

Long Term Erosion Rates: Long term

erosion rates are determined by analyzing

historical shoreline positions and

calculating annual erosion rates based

on beach survey data. Each year, DHEC

monitors over 400 survey monuments

on state beaches to conduct analysis, in

conjunction with professional coastal

engineers or shoreline researchers

from leading academic institutions.

5Common Coastal Hazards

built to current building codes.

The following section provides

information to buyers considering

beachfront property prone to

hazards, as well as guidance for

how to protect their investment.

Understand State Laws

The South Carolina Beachfront

Management Act (SC Code Ann.

§48-39-250 et seq.) was passed

by the S.C. General Assembly in

1988 to provide a more effective

framework for the management of

South Carolina’s beaches. The Act

and associated regulations establish

the state’s jurisdictional authority

within the beachfront critical

areas. Within these areas, DHEC

regulates new construction, repair,

and reconstruction of buildings

in addition to the maintenance of

erosion control structures. However,

new erosion control devices are

strictly prohibited within the setback

area. The purpose of these laws

and regulations is to protect the

quality of the coastal environment

while affording reasonable use and

development of property. State

beachfront jurisdictional lines are

unrelated to FEMA Flood Zones,

discussed in a later section.

State Beachfront Jurisdiction

The state’s beachfront jurisdictional

lines are calculated by analyzing

current and historical shoreline

positions and long-term erosion

rates. DHEC is mandated by

the South Carolina Beachfront

Management Act to review the

position of the beachfront baseline

and setback line every seven

to ten years. Since the passage

the of Beachfront Management

Act, these lines have been set

and adjusted three times, with

a fourth adjustment pending

for the 2017 revision cycle.

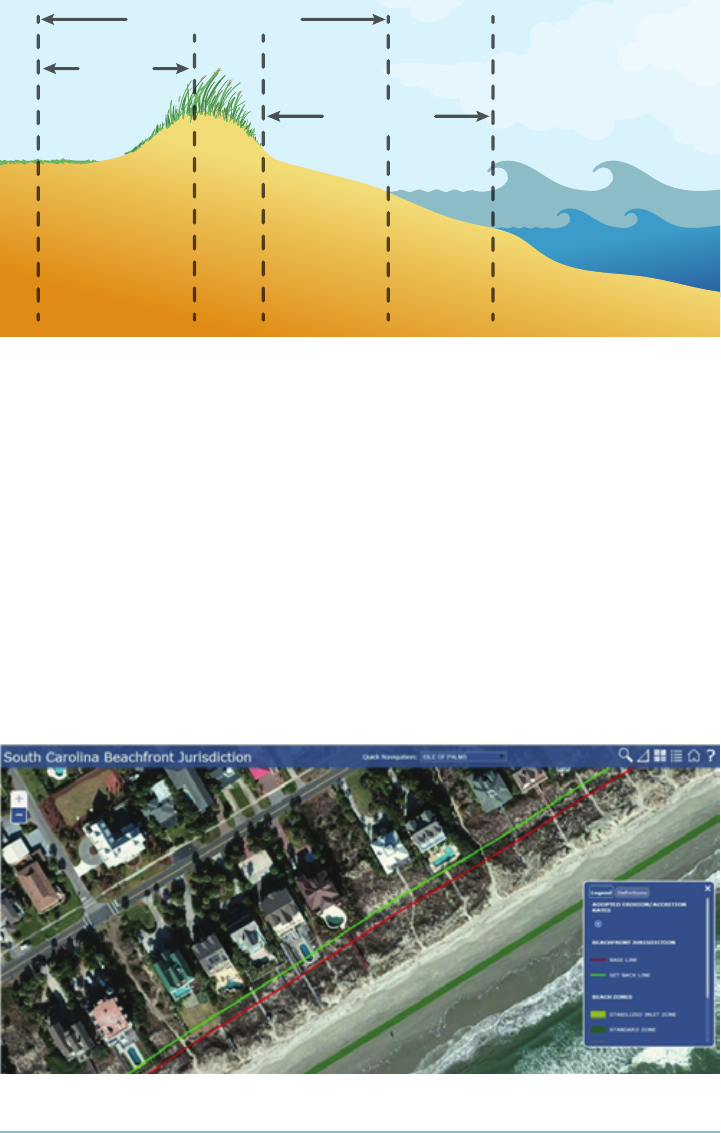

Within standard erosion zones,

the baseline is established at

the location of the crest of the

primary oceanfront sand dune.

On armored beaches and areas

without a primary sand dune,

DHEC uses scientific methods to

determine where the natural dune

would be if natural or man-made

occurrences had not interfered with

nature’s dune building process. For

inlet areas that are not stabilized

by jetties, terminal groins or

other structures, the baseline is

determined as the most landward

point of erosion at anytime during

the past 40 years. Within inlet areas

that are stabilized, the baseline is

determined by the location of the

primary oceanfront sand dune.

The setback line is established

landward of the baseline at a

distance of 40 times the beach’s

annual erosion rate. The erosion

rate is calculated using the best

available historical shoreline

position and scientific monitoring

6 South Carolina Guide to Beachfront Property

data. For example, if the erosion

rate is one foot per year, the

resulting setback line will be

positioned 40 feet landward of

the baseline. Even if a beach is

gaining sand through accretion or is

otherwise not experiencing erosion,

the setback line is always located

a minimum distance of 20 feet

landward of the baseline (Figure 3).

Determine if Erosion is an Issue

Erosion rates vary from one

municipality to another, but may

also vary significantly along a

specific beach. Due to localized

differences, it is imperative to

gather information regarding

specific erosion rates for the area

in which the property is located.

The adopted long-term erosion

Figure 4. South Carolina Beachfront Jurisdiction web application.

Available at http://gis.dhec.sc.gov/shoreline/

Active Beach

Beach/Dune System

Setback

Area

Mean Low Water

Mean HighWater

Escarpment or Line of Vegetation

Baseline = Primary Dune Crest

Setback Line = 40x Erosion Rate

Figure 3. Cross-section of beach profile, including the State’s jurisdictional baseline and setback

line in a standard zone.

7Common Coastal Hazards

rates for a specific property can be

found through the DHEC Beachfront

Jurisdiction web application

(http://gis.dhec.sc.gov/shoreline/).

The website application is a

convenient way to locate a parcel,

identify the state’s beachfront

jurisdictional baselines and

setback lines, and obtain an

adopted erosion rate for the

area of interest (Figure 4).

Ask a Licensed Real

Estate Professional

South Carolina law requires that

a contract of sale or transfer of

real property contain a disclosure

statement if a property is

affected by the state’s beachfront

jurisdictional authorities. Licensed

real estate professionals have

a fiduciary responsibility to

disclose material facts, like

the adopted erosion rates of

beachfront properties (§48-39-

330). Although agents might not

always know the erosion rates for

particular oceanfront properties,

they should provide assistance

in obtaining this information.

Research Resilience

to Large Storms

South Carolina regularly

experiences impacts from

coastal storms, including

tropical storms, hurricanes and

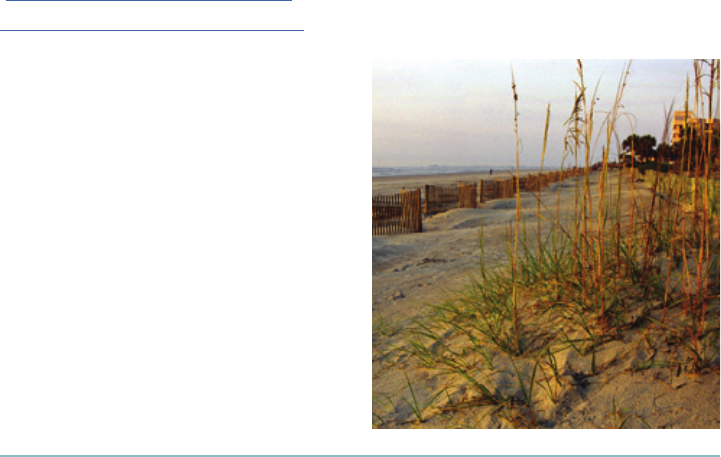

nor’easters. In 1989, Hurricane

Hugo made landfall slightly north

of Charleston, at Sullivan’s Island,

as a Category 4 hurricane, with

sustained winds of 135-140 mph.

It was the costliest storm in South

Carolina history, causing over

$7 billion in damages (National

Weather Service; Figure 5).

Even if a hurricane or other

strong storm system does not

make a direct landfall, beachfront

communities are frequently

affected by erosion caused from

storms passing offshore.

Figure 5. During Hurricane Hugo in 1989, (top) a

new inlet formed on Pawleys Island; and (bottom)

the Ben Sawyer Bridge collapsed, near Charleston,

South Carolina. Photos courtesy of NOAA.

8 South Carolina Guide to Beachfront Property

Seek Local Knowledge

Ask local residents about their

knowledge of the stability of the

beach, renourishment projects

that have been completed or

planned, flooding from storms, etc.

Their experiences and long-term

knowledge can provide valuable

insight into the area. Moreover,

archived news articles can provide

information about how the area

fared after particular storm events.

Investigate Insurance

Options & Requirements

All coastal residents should carry

homeowners insurance to protect

against the loss or damage of

personal property. It is important

to note, however, that standard

homeowner’s insurance does not

cover flood damage. Whether

building a home or buying property,

be sure to know the flood risk of

the area. Depending on the risk

associated with the property, it

is wise, and may be mandatory,

to purchase flood insurance. It

is important to note that flood

insurance only covers structures

and does not cover undeveloped

portions of property. To better

understand flood risks and

potentially reduce flood insurance

rates, locate flood insurance maps

of the area of interest and obtain an

elevation certificate to determine

the elevation of the structure

relative to the base flood elevation

of the flood zone. Additional

guidance can be sought from local

flood plain managers. Also note

that the presence or absence of

state beachfront jurisdictional

lines on a property do not reflect

risk associated with flooding

and do not affect homeowner

or flood insurance rates.

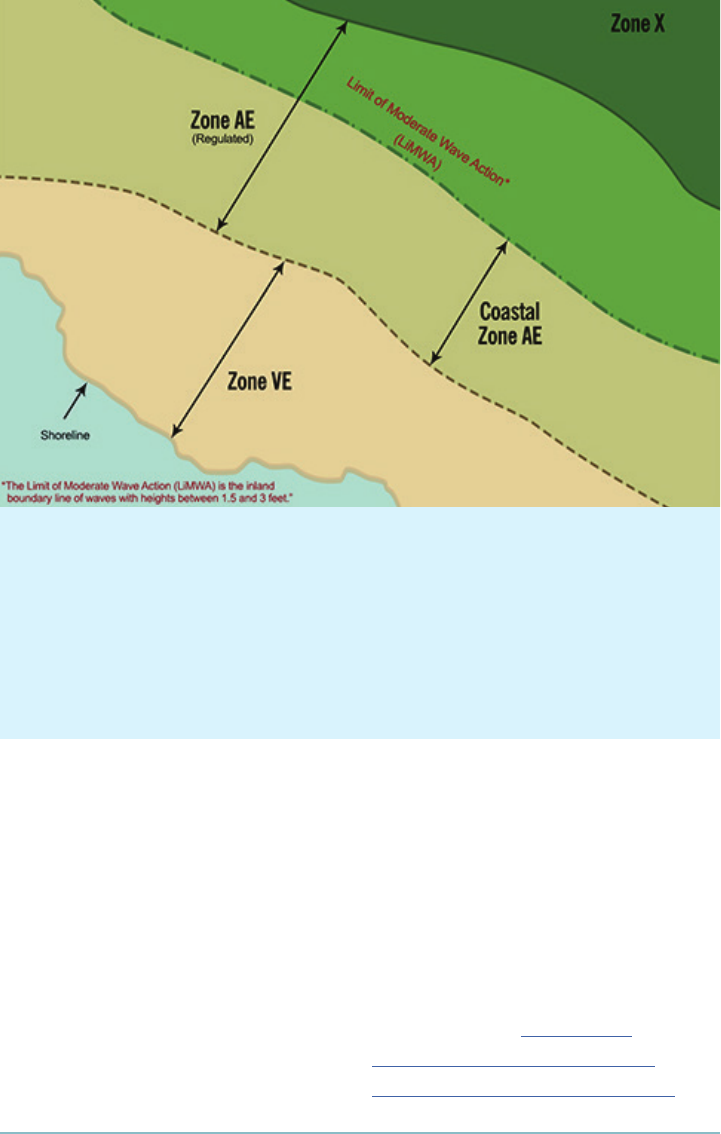

Flood Insurance Rate Maps

FEMA produces flood insurance rate

maps (FIRMs) that identify coastal

flood risk areas. FIRMs delineate

flood risk zones, Special Flood

Hazard Areas (SFHAs; Figure 6), and

identify Coastal Barrier Resources

Act (COBRA) zones. SFHAs include

Zone VE and Zone AE and have

at least a 1% chance of flooding

in any given year and a one-in-

four chance of flooding during a

typical 30-year mortgage period.

These areas take into account the

risk from storm surge and wind-

driven waves and often require

the owner to have flood insurance.

Zone X is considered a low risk

area for flooding. Purchasing flood

insurance for Zone X is usually not

required, but provides property

owners with additional protection.

9Common Coastal Hazards

As a way to minimize loss of

human life and limit damage

to natural resources within

undeveloped coastal areas,

Congress enacted the Coastal

Barrier Resources Act. The Act

identifies particular coastal barrier

resources system (CBRS) units

and Otherwise Protected Areas

(OPA), collectively called COBRA

zones. Development within COBRA

zones is permitted; however,

federal financial assistance,

including flood insurance, is not

available in COBRA zones.

Information on the flood risk

and COBRA status for a specific

property can be found on the

FEMA website (www.fema.

gov/national-flood-insurance-

program-flood-hazard-mapping).

Figure 6. Flood Risk Zones, courtesy of FEMA FloodSmart.gov

Zone VE—a high-risk area where storms

drive waves at heights of 3 feet or more.

Coastal Zone AE—a high-risk area subject

to wave heights of 1.5 to 3 feet. For flood

insurance purposes, this zone is treated

as Zone AE; however, communities are

encouraged to regulate construction

to include Zone VE standards as

these waves can still cause significant

damage to coastal structures.

Zone AE—a high-risk area subject to waves

less than 1.5 feet in height. This will be

separated from the Coastal AE zone by the

Limit of Moderate Wave Action (LiMWA).

A LiMWA may not always be present, in

which case, only Zone AE is shown.

Zone X—areas of moderate risk (shown

as a shaded zone X) or low risk (zone X).

While the risk is reduced, nearly 25% of

all flood claims come from these zones.

10 South Carolina Guide to Beachfront Property

If the property falls into a SFHA,

an insurance agent should be

contacted to discuss purchasing

a flood insurance policy.

Elevation Certificate

The elevation of a structure

compared to the estimated Base

Flood Elevation (BFE), or the

elevation to which floodwater is

anticipated to rise during a 1%

storm event, can have a major

impact on the costs of flood

insurance. The BFE of an area can

be found in the FIRM. If a current

elevation certificate is not available

for the structure, a state-licensed

surveyor will need to complete

one. To learn more about elevation

certificates, access FEMA’s

Homeowner’s Guide to Elevation

Certificates Fact Sheet

(https://www.fema.gov/media-

library/assets/documents/32330).

Changes to the National

Flood Insurance Program

Under the National Flood Insurance

Program (NFIP), many flood

insurance policy holders have

been paying federally-subsidized

rates for flood insurance that do

not reflect the true risk associated

with property and homes in flood-

prone areas. In July 2012, Congress

passed the Biggert-Waters Flood

Insurance Reform Act to make the

NFIP more financially stable by

phasing in rate increases until the

policy holder reaches the actuarial,

or non-subsidized rate. However, in

response to rapidly increasing flood

insurance costs, the Homeowner

Flood Insurance Affordability Act

was subsequently signed into law

in March 2014 to repeal and modify

some provisions of the Biggert-

Waters Flood Insurance Reform

Act. However, many provisions of

the Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance

Reform Act continue to be

implemented, affecting insurance

options for property owners.

When purchasing a home, it is

important to understand not only

what the insurance rate is at the

time of purchase, but what the full

actuarial rate will be in the future.

Contact a reputable insurance

agency and the local planning

department for more information.

11Developing on Coastal Property

BUILDING ON AN UNDEVELOPED

BEACHFRONT LOT

T

he South Carolina Beachfront

Management Act establishes

a jurisdictional area along

South Carolina’s coast where

certain activities are regulated

or prohibited. Regulations

outline specific standards for the

construction of a new home, the

repair or replacement of an existing

home, routine maintenance of an

erosion control device, and the

construction or replacement of a

swimming pool within the state’s

beachfront jurisdictional area.

Construction Seaward

of the Setback Line

The state beachfront jurisdictional

setback area is not a no-build

zone. All construction seaward of

the setback line requires a written

authorization or permit from DHEC-

OCRM before work begins. Prior to

the commencement of activities,

property owners must certify

to DHEC that any construction

meets specific conditions and

provide construction plans for

review. Within the setback area,

new habitable structures must be

built as far landward as possible

and are limited to a maximum

of 5,000 square feet of heated

space. New swimming pools may

be constructed if located behind

a functioning erosion control

device. No construction may alter

the beach’s primary sand dune or

active beach zone. Construction

of new erosion control devices

is strictly prohibited within the

setback area. To notify DHEC

of your development plans, the

Beachfront Notification Form

(www.scdhec.gov/library/D-3896.

pdf) should be submitted prior

to construction activities.

Developing on Coastal Property

If any portion of a property falls

seaward of the jurisdictional setback

line, be sure to contact DHEC Ocean

and Coastal Resource Management

before beginning construction. Failure

to do so may result in penalties and/

or require the removal of the structure

at the property owner’s expense.

12 South Carolina Guide to Beachfront Property

Construction Seaward

of the Baseline

Special Permits must be obtained

from DHEC to build seaward

of the baseline. Among other

requirements, the structure (usually

a house) must be built as far

landward as possible and have no

impact on the primary sand dune

or active beach area. Construction

of new homes seaward of the

baseline is limited to a maximum of

5,000 square feet of heated space.

Other nonhabitable structures

built seaward of the baseline

require permits, with the exception

of wooden dune walkovers less

than six feet wide. Permits are

required for wooden decks (144

square feet maximum allowed),

public fishing piers, golf courses,

and normal landscaping. If the

beach erodes and the permitted

structure becomes situated on

the active beach, the property

owner, at his or her own expense,

must remove the structure if

so ordered by DHEC. Again,

construction of new erosion control

devices within state beachfront

jurisdiction is strictly prohibited.

To obtain Special Permit

application and Beachfront

Notification Form information,

please visit our website

at www.scdhec.gov/

Environment/PermitCentral/

ApplicationForms/#OCRM.

13Developing on Coastal Property

Coastal Construction Features

Several features can prevent or

substantially reduce the likelihood

of damage from severe storms and

erosion. Pilings can be used to raise

the first floor above expected flood

elevations and storm-driven waves.

In many areas, embedding the tip of

pilings deeper than ten feet below

sea level can help to reinforce a

building to withstand the impacts of

severe erosion. Any first floor walls

constructed between pilings should

be designed to break away when hit

by waves to prevent damage to the

elevated portion of the building.

Elevating a building may

protect it from storm surge and

flooding, but it also increases its

exposure to storm winds. The

key to reducing wind damage is

in the quality of the design and

construction of the building. If

building a new home adjacent to

the beach, consider employing

the services of a professional

engineer to help ensure an

adequate structural design.

Remember, however, that no

home is disaster-proof. There

are inherent and unavoidable

dangers associated with building

homes along the beach. Because

of the substantial costs of coastal

property, a professional engineering

analysis could be a wise

investment. The Federal Emergency

Management Agency (FEMA)

also provides a comprehensive

approach to planning, siting,

designing, constructing, and

maintaining coastal property

in the Coastal Construction

Manual (FEMA P-55 - 8/2011)

(www.fema.gov/media-library-

data/20130726-1510-20490-2899/

fema55_voli_combined.pdf).

Waste Management

When building new construction,

the placement of the septic system

takes priority over location of

other structures (including the

house) and improvements. The

septic system must be set back

a minimum of 50 feet from mean

high water. Proper maintenance of

septic tanks is essential, especially

along the immediate beachfront

where spills or leaks can have

significant impacts on water quality

and the environment. Additional

information on proper waste

management can be obtained

by contacting DHEC’s Bureau of

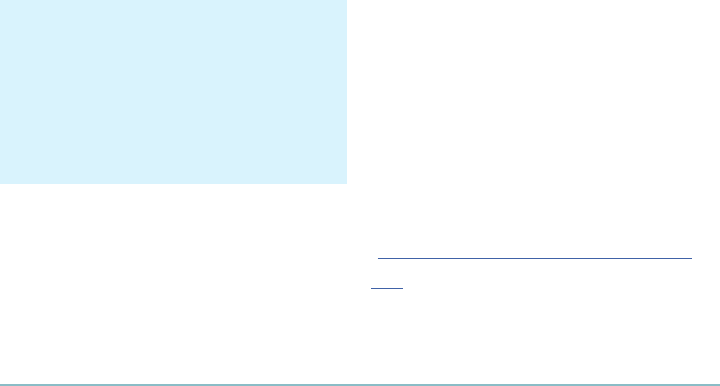

Sand dunes are natural features

that provide significant protection

during the most severe storms. It is

important to protect and enhance

dunes by keeping vehicles and people

off them, planting additional dune

grasses, and installing sand fences.

14 South Carolina Guide to Beachfront Property

Environmental Health or visiting

this website at www.scdhec.

gov/HomeAndEnvironment/

YourHomeEnvironmentaland

SafetyConcerns/SepticTanks/.

UPGRADING OR ADDING

TO BEACHFRONT HOMES

Replacement, renovations, or

additions to habitable structures

located entirely or partially in

the setback area are allowed,

subject to the criteria established

in the South Carolina Beachfront

Management Act and associated

regulations. Laws require that:

• the completed structure within

the setback area must not exceed

5,000 square feet of heated space;

• new additions must not

extend any further seaward

than the existing structure;

• the linear footage of a replaced

structure, parallel to the coast,

must not be increased.

If structural additions are entirely

landward of the setback line, notice

to DHEC-OCRM is not required

prior to construction. Contact the

local floodplain administrator and

building permit official for local

floodplain management regulations

and code requirements. It is

important to note that if the cost of

modifying a structure exceeds 50%

of the value of the structure, the

entire structure must be brought

up to current code requirements.

15Protecting & Repairing Coastal Property

B

eachfront property is vulnerable

to erosion, flooding, and

high winds. When developing a

property, being proactive by using

coastal construction features can

help reduce potential damages.

However, once a property is

developed, protecting it from

harsh beachfront conditions can

be challenging. The following

options may help protect hazard-

prone beachfront properties.

Dunes and Dune Walkovers

Beachfront property owners can

mimic and support nature by

creating sand dunes. Vegetated

sand dunes, through direct planting

or use of sand fencing, provide

some of the best protection

against high tides and minor

storms. You can learn how to

create or preserve sand dunes by

reading DHEC-OCRM’s guide, How

to Build a Dune (www.scdhec.

gov/HomeAndEnvironment/

Docs/dunes_howto.pdf).

Preserving established sand dunes

is also important. Walking on dunes

can permanently damage or destroy

them. Unnecessary wear and tear of

dunes can be prevented by building

dune walkovers. A dune walkover

may be constructed without a

permit from DHEC-OCRM if it meets

the following criteria (§48 39 290):

• constructed of wood

• no wider than 6 feet

• follows the existing dune contours

with a 2 ft. vertical clearance

• does not displace sand

• constructed with as little

environmental damage as possible

Relocation

If space allows, a structure may be

moved landward on the same lot;

otherwise, it can be relocated to

new property. Regardless of where

the building is moved, it must meet

any existing setback requirements.

Protecting & Repairing Coastal Property

16 South Carolina Guide to Beachfront Property

Safe Home Program

South Carolina has a program in

place to help property owners

mitigate for wind damage

associated with storms. The South

Carolina Safe Home Program

(http://doi.sc.gov/605/SC-Safe-

Home/) is funded through the state

wind pool and provides grants

to property owners that allow

retrofitting, or improvements

during construction of a home.

Some options for funding include

storm resistant exterior doors

(including garage doors), roof ties

and roof water barriers, bracing

gable ends, and storm shutters.

Sandbags, Sand Scraping,

and Minor Renourishment

Sandbags, sand scraping, and

minor renourishment can provide

temporary protection to structures

that are imminently threatened,

but are only allowed pursuant

to the issuance of Emergency

Orders by DHEC or authorized

municipal government officials

acting to protect public health

and safety (§48 39 130(D)(1)). A

structure is determined to be in

imminent danger when the erosion

comes within twenty feet.

Sandbags

Current regulations require

sandbags to be no larger than five

gallons (or 0.66 cubic feet), unless

otherwise approved by DHEC-

OCRM. Sandbags may not be

placed any farther seaward than

necessary to protect the structure

and must be stacked at a 45 degree

angle. Most importantly, sandbags

may only be filled with clean

beach-compatible sand that can be

returned back to the beach when

the bags are removed. The property

owner is responsible for the day-to-

day maintenance of the sandbags,

as well as removal (R.30-15(H)(1)).

Sand Scraping

Property owners may also protect

their homes by bulldozing sand, or

sand scraping, to create temporary

dunes. Sand may only be scraped

from the intertidal beach and

only between extended property

lines of the structure receiving

the sand. The depth of scraping

may not exceed one foot below

existing beach level. Sand may

be placed against an eroded

escarpment or to replace an eroded

dune, but may not be placed

in front of a functional erosion

control structure (R.30-15(H)(2)).

17Protecting & Repairing Coastal Property

Minor Renourishment

Minor beach renourishment can

protect a structure in imminent

danger and potentially slow

erosion. When renourishing,

property owners must use sand that

originates from an upland source

and is approved by DHEC-OCRM as

being beach compatible. Sand must

be placed between the extended

property lines of the affected

property, and may be stabilized

with sand fencing and beach

vegetation pursuant to permitting

requirements (R.30-15(H)(3)).

Erosion Control Structures

Hard erosion control structures

represent the greatest threat to

the preservation of the beach.

On an eroding beach, seawalls

and rock revetments actually

accelerate erosion by reflecting

wave energy and scouring sand

away from the active beach. South

Carolina applies a strict regulatory

position where these structures are

concerned; no new erosion control

structures may be constructed

seaward of the setback line.

Although new erosion control

devices cannot be constructed,

existing functional devices may

be maintained and repaired in

certain circumstances. Functional

erosion control structures may

not be enlarged, strengthened or

rebuilt, but may be maintained in

their present condition. Notably,

if destroyed more than 50%, the

entire structure must be removed at

the owner’s expense (§48 39 290).

RECOVERY AFTER A STORM

Repairing and Rebuilding

Following a storm event,

habitable structures within

the state’s jurisdiction may be

repaired or rebuilt in accordance

with the following criteria:

• the square footage of the

replacement structure seaward

of the setback line cannot exceed

the total square footage of the

original seaward structure

• the linear feet parallel to the

coast must not exceed the

original linear footprint

• where possible, the replacement

structure must be moved

landward of the setback line,

or if not possible, must be

moved as far landward as

practical, considering zoning

and parking regulations

• the structure must meet locally

defined ordinances required

for flood damage prevention

as required by the NFIP

18 South Carolina Guide to Beachfront Property

• the entire structure must be

brought up to code if the cost

of repairs/replacement exceeds

50% of the structure’s value

• Pools that are damaged or

destroyed may be rebuilt to

preexisting dimensions with

authorization from DHEC.

Destroyed Beyond Repair

Following a major storm event,

structure(s) located along the

shoreline may be severely damaged

and declared “Destroyed Beyond

Repair” (DBR). For habitable

structures and pools, destroyed

beyond repair means more than

66 2/3% of the replacement value

of the habitable structure or pool

has been destroyed (R.30-14(D)(3)

(a)). A structure that is destroyed

beyond repair due to man-made

causes can be rebuilt provided the

new structure is no larger than the

original structure it replaces, and

is constructed as far landward as

possible. The new structure must

not be farther seaward than the

original structure (R.30-13(E)(6)).

For seawalls, bulkheads, and

revetments, damage must be

judged on the percentage of the

structure remaining intact, above

grade, at the time of the damage

assessment. If more than 50% of the

erosion control structure or device

has been destroyed, it must not be

repaired or replaced (R.30-14(D)

(3)(c)). For additional information

regarding the evaluation of

damage and requirements for

rebuilding, see the Coastal

Division Regulations 30-14(D).

***

In summary, this guide is

designed to provide general, yet

important information regarding

the purchase and ownership of

beachfront property in South

Carolina. However, it does not

address all situations that may

impact a particular property. It is

important to obtain all pertinent

information from federal,

state, and local authorities.

20 South Carolina Guide to Beachfront Property

Additional Information & Contacts

DHEC Office of Ocean and Coastal

Resource Management

www.scdhec.gov/ocrm

Charleston

1362 McMillan Ave., Suite 400

Charleston, SC 29405

(843) 953-0200

Myrtle Beach

927 Shine Ave.

Myrtle Beach, SC 29577

(843) 238-4528

Beaufort

104 Parker Drive

Beaufort, SC 29906

(843) 846-9810

Federal Emergency Management

Agency (FEMA)

www.fema.gov

(202) 646-4600

National Flood Insurance Program

(NFIP)

www.floodalert.fema.gov

1-800-638-6620

SC Department of Natural

Resources Flood Mitigation

Program

www.dnr.sc.gov/water/flood/index.html

(803) 734-9120

SC Sea Grant Consortium

www.scseagrant.org

(843) 953-2078

SC Department of Insurance,

Consumer Services Division

www.doi.sc.gov

(803) 737-6180

SC Wind and Hail Underwriting

Association

www.scwind.com

(803) 779-8373

SC Safe Home

www.doi.sc.gov/605/SC-Safe-Home/

(803)737-6087

SC Real Estate Commission

www.llr.state.sc.us/POL/REC/

(803) 896-4400

US Army Corps of Engineers/

Charleston District, Public Affairs

Office

www.sac.usace.army.mil

(843) 329-8123

US Geological Survey – South

Carolina Earthquake Information

www.earthquake.usgs.gov/

earthquakes/states/index.

php?regionID=40

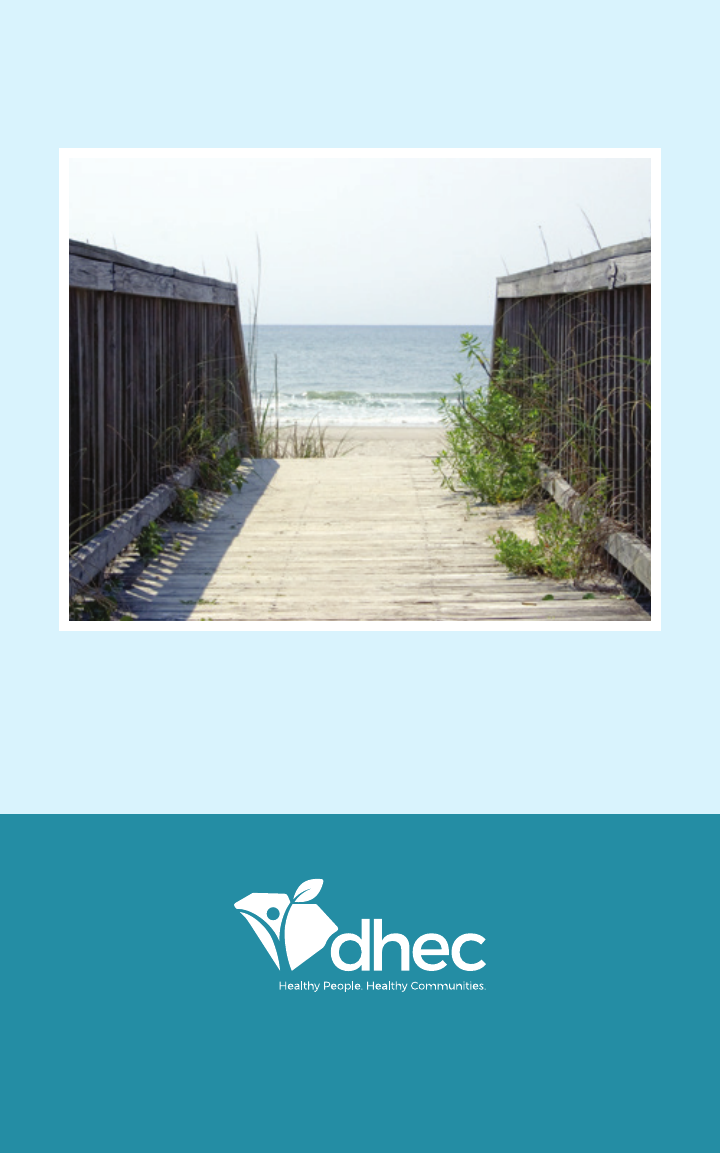

1-888-ASK-USGS

The information in this publication is intended to be a helpful guide for purchasing coastal real estate.

Since every property is unique and local codes may vary, be sure to consult your real estate professional before

making a decision. Also, if you have questions about particular aspects of a property, be sure to contact the

appropriate state and federal agencies.

21Acknowledgements

Contributing Organizations

ACE Basin National Estuarine Research

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control

South Carolina Department of Natural Resources

S.C. Sea Grant Consortium

www.scdhec.gov

CR-003559 12/17