Pet Policy and Housing Prices: Evidence from the Condominium Market

Zhenguo Lin

Department of Finance

California State University, Fullerton

CA 92831-3599

Marcus T. Allen

Carter Real Estate Center

School of Business and Economics

College of Charleston

Charleston, South Carolina 29401

Charles C. Carter

Haint Blue Realty, LLC

9034 S.W. 7

th

Street

Boca Raton, Florida 33433

Abstract

This paper examines the economic impact of restrictions against keeping domestic

pets in residential dwellings. Using a large data sample of condominium sales, we

empirically estimate price effects associated with pet restrictions. Our results

suggest that an unrestricted pet policy creates a significant premium in

condominium price, along with discounts for condominiums that do not allow

pets or have pet restrictions. This finding is useful for policy makers, developers

of new condominium projects, and condominium owner associations in their

decisions to establish or alter laws and regulations regarding restrictions on pet

owner residents.

August 8, 2011

1

Pet Policy and Housing Prices: Evidence from the Condominium Market

[Abstract] This paper examines the economic impact of restrictions against

keeping domestic pets in residential dwellings. Using a large data sample of

condominium sales, we empirically estimate price effects associated with pet

restrictions. Our results suggest that an unrestricted pet policy creates a significant

premium in condominium price, along with discounts for condominiums that do

not allow pets or have pet restrictions. This finding is useful for policy makers,

developers of new condominium projects, and condominium owner associations

in their decisions to establish or alter laws and regulations regarding restrictions

on pet owner residents.

Data reported by the American Pet Products Association (APPA) indicates that

pet ownership in the United States increased by almost 3 percent between 2005 and 2007

(Ferrante (2007)) resulting in an all-time high of 71.1 million households owning at least

one domestic pet. Between 1997 and 2007, the number of U.S. households grew by 14

percent, while the number of pet-owning households grew by 22 percent. The APPA

(2008) estimates that total expenditures by pet owners on household pet health and

nutrition was $41.2 billion in 2007, with $16.2 billion spent on food, $10.1 billion spent

on veterinary care, $9.8 billion spent on supplies and over-the-counter medicine, $2.1

billion on live animal purchases, and $3.0 billion spent on grooming and boarding. The

rise in pet ownership and pet related expenditures is attributable to the perceived or real

satisfaction enjoyed by individuals related to pet ownership, presumably due to increased

health, safety, security, or other benefits of sharing one’s life with a pet.

Along with the increased incidence of pet ownership, some pet ownership

advocates are pushing to eliminate or at least reduce restrictions on pets in residential

dwellings. While federal laws already prohibit discrimination in housing and other

public accommodations against mentally and physically disabled persons regarding

2

“service and support” animals, efforts are underway to extend this protection to all

individuals who wish to keep “companion” or “emotional support” animals in their

dwellings even though these individuals do not have disabilities protected by federal laws.

The strategy adopted by some proponents of such a policy change is to appeal to the

medical and psychological benefits that may accrue to pet owners, regardless of their

disability (or lack thereof) status.

Irrespective of political and/or emotional motivations for eliminating or reducing

restrictions against pet ownership in residential dwellings, the primary purpose of the

current study is to consider the price effects of pet restrictions using a sample of

condominium transactions from the Fort Lauderdale, Florida metropolitan area. The

research question considered is whether or not relationships can be detected between

condominium prices and pet restrictions such as “no pets of any kind,” “small pets only,”

“large pets only,” “dogs only,” and “cats only.” Previous research on the effect of pet

restrictions on condominium prices suggests that allowing cats is related to increased

prices, but that prices are negatively related to allowing dogs. Previous research on the

effect of pet restrictions on multi-family apartment rents suggests that pet restrictions

have no significant rent effect. This study extends prior research on pet policies and

condominium prices to a different geographic area, a more current time period, and a

much larger sample of observations.

The next section of this paper reviews the legalities and politics involved in the

initiative to reduce or even eliminate restrictions on pet ownership in dwelling units. In

Section 2, we develop a model to study the economic impact of pet policy on housing

prices. The third section describes the methods used in this study to empirically examine

3

the price effects of pet restrictions. The fourth section discusses the results of the analyses.

The final section provides interpretations and potential policy directions suggested by the

results of this study.

1. The Legalities and Politics of Pet Restrictions

The federal Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988, Section 504 of the

Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act protect

against discrimination of persons who need the assistance of service or support animals

as a result of conditions that substantially limit major life activities. This protection from

discrimination has been upheld in various courts. The 7th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled

in favor of a deaf person’s right to keep a service/support animal in a dwelling, opining

that:

“[b]alanced against a landlord’s economic or aesthetic concerns as

expressed in a no-pets policy, a deaf individual’s need for the

accommodation afforded by a hearing dog is, we think, per se reasonable

within the meaning of the” Fair Housing Act. (Bronk v. Ineichen, 54 F.3d

425, 429 (7

th

Cir. 1995)).

A similar ruling was handed down by the U.S District Court of Oregon in Green v.

Housing Authority of Clackamas County, 994 F.Supp. 1253 (Or. 1998). In 2003,

however, a court ruled against the plaintiff on the grounds that the animal possessed “no

abilities assignable to the breed or to dogs in general” that would assist the plaintiff

(Prindable v. Ass’n of Apartment Owners of 2987 Kalakaua, 304 F. Supp. 2d 1245, 1256-

57 (D. Hawaii 2003)). In 2004, another court rejected the plaintiff’s claim to the right of

a service or support animal on the grounds that the plaintiff could not sufficiently prove

that such an animal would provide the needed benefits (Oras v. Housing Authority of City

4

of Bayonne, 861 A.2d 194,203 (N.J. Super. Ct. 2004)). Each of these rulings are

premised on the idea “…that the animal be (1) individually trained, and (2) work for the

benefit of an individual with a disability” (Poliakof (2008)).

Going beyond accommodation for disabilities, federal law provides some

protection for the elderly whose emotional support is enhanced by ownership of pets.

Part of the Housing and Urban-Rural Recovery Act of 1983 includes a rule titled Pet

Ownership in Assisted Rental Housing for the Elderly or Handicapped (POEH) (12

U.S.C. § 1701r-1 (2000)). The legislation recognizes the support that pets can provide

the elderly by providing that owners and managers of federally assisted housing for the

elderly or handicapped cannot prohibit or prevent tenants from owning common

household pets. The rule applies only to those apartments receiving federal subsidies, but

it nonetheless reflects the benefits expected for elderly residents from the accompaniment

of pets.

At the state legislative level, California enacted a law effective January, 2001,

(California Civil Code Section 1360.5) that permits each owner in common interest

developments (such as condominiums and mobile home parks) to keep at least one pet,

subject to reasonable rules and regulations of the homeowners’ association. Notably, the

California law makes no reference to the owner’s need for a mental or physical disability,

instead permitting pets for all owners who desire to maintain a pet in their common

interest home. Efforts are underway in Florida to adopt similar legislation, though this

legislation does make reference to need beyond simply the preference for a household pet

in condominium properties.

5

In Florida, Citizens for Pets in Condos, Inc., a non-profit organization, is lobbying

for consideration of a proposed bill (Emotional Support Animal Bill) in the state

legislature that would permit “emotional support” animals in condominiums throughout

the state. Anyone with approval from a qualified medical professional, regardless of the

disabilities recognized in federal law, who could benefit from having an emotional

support animal, could keep a pet in their dwelling regardless of community or

homeowner association rules. The proposed law in Florida would allow a variety of

medical professionals (doctors, nurses, social workers, etc.) to grant approval for

individuals who express a preference to maintain a pet in their condominium unit,

effectively overriding condo association rules against pets in the units.

The bill proposed by the Citizens for Pets In Condos group died in committee

during the 2007 legislative session and was not considered by the legislature in 2008,

2009, or 2010, due to the lack of a sponsor of the bill in the state senate. Even so, the

group’s efforts are continuing as of this writing and there is some probability, given the

widely-held opinion of a need for condominium association reform that currently exists

in Florida, that the legislation will eventually make it to the floor of the legislature. (See

http://petsincondos.org for a current update on the group’s activities to promote their

cause as part of the broader effort to reform condominium association regulations).

Supporters of legislation prohibiting pet restrictions in dwelling units frequently

cite the physical and emotional health benefits of pet ownership reported in numerous

research studies conducted or supported by such entities as the Center for Disease

Control, U.S. Department of Health, American Association of Retired Persons, American

Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, Humane Society of the United States,

6

American Heart Association, and Baker Medical Research Institute, as well as numerous

research reports published in a variety of research outlets. For examples of such research

reports, see (among many others) Allen, et al. (1991), Barker and Dawson (1998),

Duncan (2000), Endenburg, ‘t Hart, and Bouw (1994), Hirschman (1994), Mallia (2006),

and Raina, et al. (1999), and Schwarz, Troyer, and Walker (2007).

Opponents, or at the very least, non-supporters, of the proposed Florida bill

maintain that individual owner associations should be entitled to democratically

determine, within the associations’ bylaws, whether pet ownership rights are a desirable

“amenity” of the condominium community. Possible negative effects cited by opponents

of the Florida bill include odor, noise, waste disposal, and damage to the common areas

of the property.

On the presumption that housing market dynamics should determine the economic

effect of pet restrictions on condominium prices, a statistically rigorous analysis of the

potential relationship between prices and pet restrictions may provide market-supported

evidence of the price effects of pet restrictions. The results may be used by one side of

this debate or the other to bolster its position and to possibly affect decisions of

developers, owner associations, and policy makers regarding pet restrictions.

2. The Model

To study the economic impact of a particular pet policy on housing prices, we

develop a simple model based on a set of equations proposed by Malpezzi and

Maclennan (2001):

DPQ

D 210

(1)

7

PQ

S 10

(2)

SD

QQ (3)

The variables in Equations (1) – (3) are defined as follows:

D

Q

is housing demand,

P

is

house price, and D is a demand factor that is determined by demand variables such as

income and population.

S

Q is housing supply.

1

(

1

) represents the price elasticity of

housing supply (housing demand).

By equating supply and demand in Equation (3) and solving for the house price,

we can obtain a reduced form of the system,

DP

11

2

11

00

(4)

Now suppose that a pet policy

i

pp is introduced in the housing market. Assume

that this policy immediately affects the demand side: buyers who like the policy will have

higher values for properties with such a policy. The demand function (1) then becomes

)()(

210 iiD

ppDPppQ

(5)

Since the buyers who like the policy are less sensitive to price increase, we thus have

11

)(

i

pp . Suppose that the supply function (2) stays the same for the moment. From

Equations (2) and (3), we can rewrite Equation (4) as,

)(

)()(

)(

11

2

11

00

i

ii

i

ppD

pppp

ppP

(6)

If the demand factor does not change, i.e., DppD

i

)( , the difference between Equations

(4) and (6) yields,

0

))()((

))()((

)(

1111

11200

i

i

i

pp

ppD

ppPP

(7)

8

Equation (7) suggests that the pet policy

i

pp will result in a higher house price, i.e.

PppP

i

)( . Now suppose that the pet policy causes the demand factor to change. When

)(

))()(())((

)(

11

110011

ii

i

ppDpp

ppD

, we can show that

0)(

i

ppPP (8)

Equation (8) implies that the pet policy

i

pp may also result in a lower house price, i.e.

PppP

i

)( , if the pet policy reduces the demand factor significantly.

Thus far, we assume that the pet policy

i

pp does not affect the supply function

(2). Generally speaking, the pet policy may also affect the supply side. If this is the case,

we can similarly show that housing prices will decrease (or increase) if there is

oversupply (or less supply) of houses with such pet policy. In sum, the model suggests

that the impact of a particular pet policy on housing prices can be positive or negative

depending on the changes of supply and demand due to the pet policy. In other words,

whether pet restrictions create a premium in housing prices becomes an empirical

question. By using a large data sample of condominium sales in the Fort Lauderdale,

Florida metropolitan area, we will provide an answer to this question in the next section.

3. Data Description and Empirical Model

Previous empirical research on the relationship between pet restrictions and

housing prices (and rents) includes Sirmans, Sirmans, and Benjamin (1989) and

Cannaday (1994).

1

Sirmans, Sirmans and Benjamin report no statistically significant

1

The Cannaday (1994) article also cites a study done by the Minnesota Real Estate Research Center (1990)

on renters whose empirical findings were the same (cats “yes,” dogs “no”).

9

relationship at even the 10 percent level between “no pets” restrictions and multi-family

rents using a sample of 188 apartment rental transactions from 92 apartment complexes

in Lafayette, Louisiana. All observations were of rents, physical characteristics, location,

amenities, services, occupancy restrictions, and external factors as of September 1986.

The amenity in question was the allowance or disallowance of pets, without

discrimination between dogs and cats. Cannaday’s analysis employs a data sample of

1,061 condominium sales that occurred in Chicago between 1988 and 1991, and

considers four types of pet restrictions: no pets allowed, cats only allowed, small dogs

allowed, and large dogs allowed. He concludes that in the market area and time period he

studied, condo prices are positively related to “cats allowed,” but negatively related to

“dogs allowed,” and that the net effect on prices related to pet restrictions ultimately

depends on what type of pets are allowed.

Extending previous analysis to a different market, a larger sample, a more recent

time period, and slightly different pet policies, a sample of condominium sales drawn

from the local MLS for the Fort Lauderdale, Florida metropolitan area, the present study

provides a sizeable data sample for analyzing the relationship between pet restrictions

and condominium prices. The sample collected for this study contains 19,324

condominium transactions that occurred between the 1

st

quarter of 2005 and the 2

nd

quarter of 2007 with sufficient information regarding the selected independent variables

to be included in the analysis. Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for variables from

the condominium transactions used in the analysis, while Table 1 gives definitions for

those variables.

10

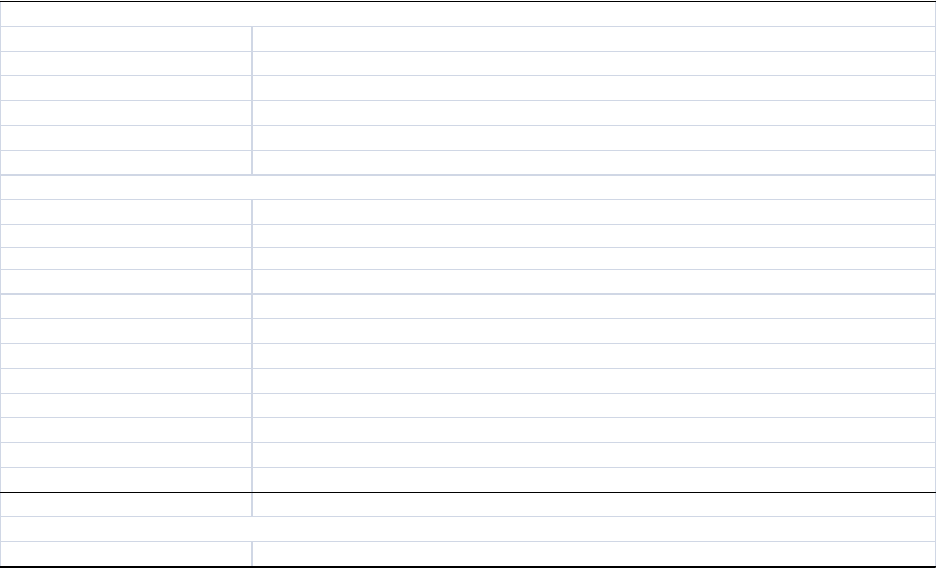

Table 1: Variables Definitions

age Age of the unit.

age2 Squared age.

beds # of bedrooms.

baths # of bathrooms.

style Codes indicating property style.

waterfr yes if the property is exposed to waterfront.

area

MLS-defined, corres

p

ondin

g

to housin

g

sub-markets; more than 120 areas in our datase

t

income median household income ($) on the zipcode level

vacant yes if the proeprty is vacant.

mom months on the market.

yq year and month of the sale.

pets_allowed yes if the property allows pets.

pets_allowed_with_restriction yes if the property allows pets with certain restrictions.

cats_only yes if the property only allows cats.

dogs_only yes if the property only allows dogs.

small_pets_only yes if the property only allows small pets less than 20 pounds.

large_pets_only yes if the property only allows large pets heavier than 20 pounds.

ln(P) Sale price in natural logarithm.

Dependent Variable

Condo Property Characteristics Variables

Neighborhood Characteristic, Location and Other Variables

11

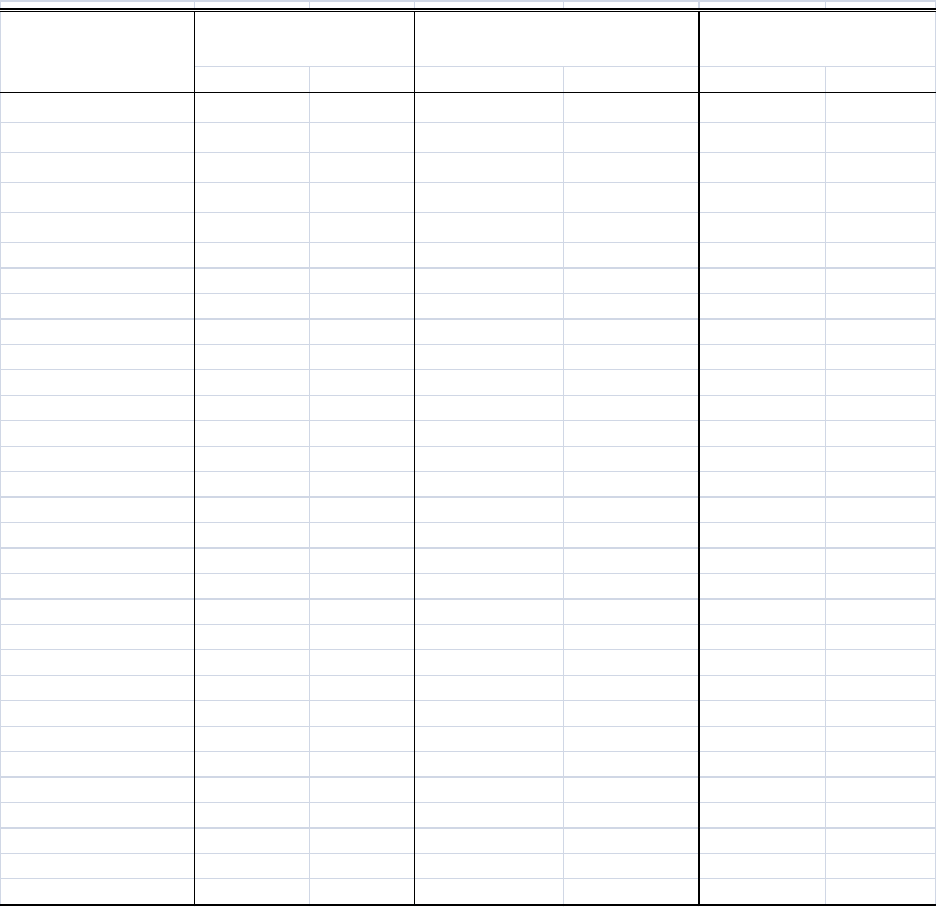

Table 2: Summary Statistics

Mean Std Dev. Mean Std Dev. Mean Std Dev.

age

24.00 10.74 19.92 11.89 20.32 11.83

age2

691.28 442.87 538.33 451.98 552.74 453.73

beds

1.89 0.64 2.03 0.69 2.01 0.68

baths

1.83 0.50 1.90 0.58 1.88 0.57

waterfr

0.415 0.493 0.394 0.489 0.397 0.489

vacant 0.40 0.49 0.37 0.48 0.37 0.48

mom 2.31 2.29 2.27 2.28 2.26 2.29

style (%)

1-4 story condo 59.3% 54.0% 55.7%

5+ story condo 28.5% 24.1% 24.8%

townhouse condo 9.5% 17.6% 15.6%

villa condo 2.7% 4.3% 3.9%

pet restrictions (obs)

cats only 634

dogs only 160

small pets only 2,918

large pets onlys 1,895

others (unspecified) 3,003

income $44,806.6 $10,994.8 $47,915.9 $12,361.5 $47,786.1 $12,108.0

Sale Price $235,600.2 $194,358.4 $283,567.1 $232,877.5 $280,364.6 $228,670.2

Time of Sale (%)

2005Q1 0.6% 0.7% 0.7%

2005Q2 9.7% 8.8% 9.0%

2005Q3 17.1% 16.8% 17.0%

2005Q4 10.9% 11.0% 10.9%

2006Q1 14.9% 15.7% 15.5%

2006Q2 12.6% 13.1% 13.1%

2006Q3 10.1% 10.9% 10.7%

2006Q4 9.0% 8.8% 8.6%

2007Q1 10.3% 9.5% 9.8%

2007Q2 5.0% 4.7% 4.8%

Variables

N=19,324

Full Sample

N=9,748

Pet allowed w/ or w/o restrictions

N=8,610

Pet allowed w/ restrictions

The method of analysis is the familiar hedonic pricing model with the natural log

of transaction price as the dependent variable and property/market/amenity characteristics

as independent variables. The available information from the MLS regarding

condominiums in this market area permits analysis of (1) “no pets allowed,” (2) “any pets

12

allowed,” (3) “pets allowed with some restrictions,” (4) “only small pets allowed,” (5)

“only big pets allowed,” (6) “only dogs allowed,” and (7) “only cats allowed” pet policies.

Using the full sample, the first specification is:

allowedpetsCmom

NAgeAgeLSP

_

)ln(

876

5

2

43210

(9)

where P is the condominium price; S denotes a set of structural characteristics; L is the

location control variable. There are over 120 MLS-defined areas in the Fort Lauderdale,

Florida metropolitan area. In the opinion of brokers, the MLS-defined areas generally

correspond to housing submarkets. Similar to Carter et al (2011), we used these MLS-

defined areas to control for location. Age and Age Squared are included to account for the

possible nonlinear effect due to higher likelihood of renovations as dwellings age

(Goodman and Thibodeau (1997)); N controls for neighborhood effects; mom controls for

months on the market since listing (Cheng, Lin and Liu (2008)); C is a vector of

year/quarter of sale to control for seasonal effect and market conditions. Pets_allowed is

the dummy variable indicating whether any pets are allowed on the property.

The second specification estimates a similar model using a subsample of

pets allowed w/ or w/o restrictions to examine the impact of “pets allowed with

restrictions” on sales prices:

nsrestrictiowithallowedpetsCmom

NAgeAgeLSP

___

)ln(

876

5

2

43210

(10)

The third specification is used to estimate how different “pet restriction”

policies, such as cats only, dogs only, small pets only, large pets only, and others,

affect sales price. In our sample the categories of cats only, dogs only, small pets

13

only, large pets only, and the others (unspecified) are mutually exclusive.

2

So,

the estimation sample is the subsample of pets allowed with restrictions and the

model can be rewritten as follows:

onlycats

onlydogsye_pets_onllonlypetssmall

CmomNAgeAgeLSP

_

_arg__

)ln(

11

1098

765

2

43210

(11)

Variables of interest are the coefficients for pets_allowed in the first specification,

pets_allowed_with_restrictions in the second specification, and small_pets_only,

large_pets_only, dogs_only, and cats_only in the third specification. Following Kennedy

(1984), the percentage change of housing price (g) due to these pet policies can be

calculated as follows:

100*]1))var(

2

1

[exp(

g

(12)

4. Regression Analysis

What distinguishes the housing market here under investigation from those of

previous studies is that it is largely a retirement community. South Florida is renowned

for being a place where seniors retire, and its housing market has been used in studies of

age-restricted housing (Allen (1997); Carter, et al. (2011)), as has Phoenix, Arizona

(Guntermann and Moon (2002), Guntermann and Thomas (2004) and Lin, Liu and Yao

(2010)). Federal legislation takes cognizance of the favorable influence of pets on

seniors in the Pet Ownership in Assisted Rental Housing for the Elderly and Handicapped

Act, mentioned above. Therefore, for condominiums in a retirement area such as South

2

Table 2 illustrates that among 8,610 observations in the sample, “cats only” has 634 observations, “dogs

only” has 160 observations, “small pets only” has 2,918 observations, “large pets only” has 1,895

observations and “others (unspecified)” has 3003 observations.

14

Florida there could be significant demand for an unrestricted pet policy. Accordingly, a

price premium is expected for allowance of pets in South Florida housing.

The empirical results are shown in Table 3. The coefficient of interest for the first

equation, pets_allowed, is 0.110 (a price premium of 11.6%),

3

statistically significant at

the 1% level, showing sales of condominiums with pets allowed with no or certain

restrictions during the observed period sell for 11.6% more than other condominiums

with no pets allowed, ceteris paribus. The coefficient for pets_allowed_with_restrictions

in the second equation is - 0.0132 (a discount of 1.3%),

4

significant at the 5% level,

demonstrating that sales of condominiums with pets allowed with certain restrictions

during the observed period suffer a price discount of 1.3% compared with other

condominiums with pets allowed with no restrictions , ceteris paribus. In the third

specification, the coefficients for cats_only, small_pets_only, dogs_only, and

large_pets_only are all negative, they are -0.071, -0.024, -0.002, and -0.004, respectively,

and the first two are significant at the 1% level. This result suggests condominiums with

cats_only and small_pets_only suffer most in price discount. Overall, we can conclude

that unrestricted pet policy creates a significant premium in condominium price, along

with discounts for condominiums that do not allow pets or have certain restrictions on

pets (cats_only and small_pets_only).

The R-squares show that the models are reasonably good fits for each of the

estimated price equations, at R

2

= 89.5 percent for the first specification (where the

number of observations was 19,324), R

2

= 89.1 percent for the second specification

(where the number of observations was 9,748), and R

2

= 89.3 percent for the third

3

11.6% is estimated using Equation (12).

4

A discount of 1.3% is estimated by using Equation (12).

15

specification (where the number of observations was 8,610). Other coefficients are

consistent with prior expectations. For example, coefficients on beds and baths are

positive and highly significant. Waterfront (waterfr) properties sell for more while

vacant (vacant) condominiums sell for less. The coefficient for age is negative and highly

significant, because a house depreciates as it ages. The age-squared term has a positive

effect on housing price, reflecting nonlinearity and vintage effect. Higher floors are

associated with price premiums. This result is consistent with the findings by So, Tse and

Ganesan (1997). The coefficients for Year and Quarter of Sale are all highly significant

and follow a distinct pattern from 2005 to 2007. Starting in 2005Q1 the coefficient is

negative, then switches to positive in 2005Q2, then grows over the next three quarters

before falling over the last four quarters. This demonstrates that housing market

conditions were changing constantly during that time period in South Florida.

5

5

At the suggestion of an anonymous reviewer, we tested for spatial autocorrelation using Moran’s I method

(Moran (1950)). The tests failed to reject the null hypothesis of zero spatial autocorrelation, indicating

there the 120 location control variables in our specifications have adequately addressed the possibility of

spatial autocorrelation. The results of the Moran’s I tests are available upon request.

16

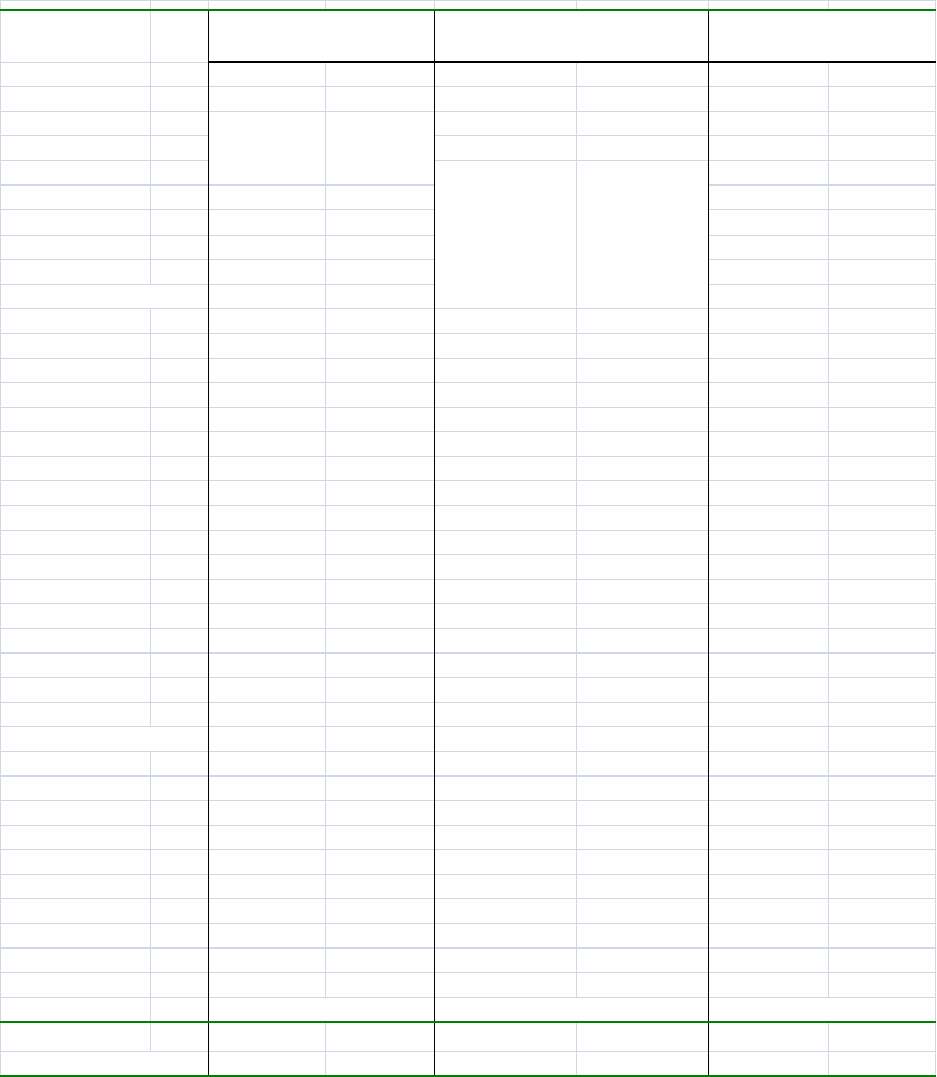

Table 3: Regression Results

Coefficient T-Stat. Coefficient T-Stat. Coefficient T-Stat.

Intercept

10.955*** 59.31 10.556 44.17 10.864 44.32

Pet Allowed

(yes)

w/o restriction

w/ restriction

(yes)

cats only -0.071*** -8.20

small pets only -0.024*** -4.94

large pets only -0.002 -0.42

dogs only -0.004 -0.27

others (unspecified) 0.000 .

age

-0.012*** -20.13 -0.014*** -19.36 -0.013*** -17.41

age2

0.000048*** 3.35 0.000113*** 6.11 0.000104*** 5.29

beds

0.192*** 54.50 0.159*** 36.94 0.156*** 34.04

baths

0.21*** 46.04 0.220*** 41.45 0.221*** 39.06

waterfr

(yes) 0.079*** 24.12 0.081*** 18.06 0.079*** 16.77

vacant

(yes) -0.032*** -11.01 -0.013*** -3.23 -0.014*** -3.48

tom

0.002*** 3.15 0.006*** 6.92 0.006*** 6.52

style

1-4 story condo

-0.148*** -15.06 -0.133*** -12.36 -0.128*** -10.86

5+ story condo

-0.076*** -7.01 -0.067*** -5.22 -0.065*** -4.72

townhouse condo

-0.120*** -12.20 -0.101*** -9.84 -0.104*** -9.2

villa condo

0.000 . 0.000 . 0.000 .

floor level

<= 6

0.000 . 0.000 . 0.000 .

7-15

0.084*** 5.42 0.068*** 3.39 0.071*** 2.90

>=16

0.154*** 12.45 0.148*** 9.92 0.141*** 8.40

log(income)

0.122*** 10.45 0.163*** 11.37 0.134*** 8.69

Year and Quarter of Sale

2005Q1

-0.085*** -3.87 -0.07** -2.4 -0.104*** -3.30

2005Q2

0.051*** 6.48 0.028*** 2.6 0.026** 2.31

2005Q3

0.101*** 13.87 0.076*** 7.66 0.077*** 7.39

2005Q4

0.141*** 18.4 0.100*** 9.75 0.104*** 9.58

2006Q1

0.148*** 20.34 0.122*** 12.53 0.123*** 11.97

2006Q2

0.134*** 18.14 0.109*** 10.97 0.115*** 11.08

2006Q3

0.103*** 13.53 0.074*** 7.3 0.075*** 6.98

2006Q4

0.069*** 8.98 0.050*** 4.83 0.052*** 4.74

2007Q1

0.041*** 5.53 0.044*** 4.26 0.040*** 3.77

2007Q2

0.000 . 0.000 . 0.000 .

Location control

R

2

89.5% 89.1% 89.3%

19,324 9,748 8,610Number of Obs.

Subsample II

Pet allowed w/ restrictions

Yes Yes Yes

0.110*** 30.20

-0.0132** -2.25

Full Sample

Pet allowed or not allowed

Subsample I

Pet allowed w/ or w/o restrictions

Note: Statistical significance is indicated as follows: *** at the 1% level and ** at the 5% level.

Dependent variable is sale price in natural logarithm. The coefficients for over 120 binary

location variables are omitted for brevity.

17

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

While there are certainly emotional and disability-related reasons why people

prefer to have pets in their homes, the analysis presented in this study suggests that

condominium prices are significantly related to pet policies. To the extent that these

results support the contentions of anti-restriction activists, condominium developers and

owner associations might well consider changing existing prohibitions against certain

types of pets (or maintaining the status quo in the absence of such restrictions) in pursuit

of enhanced property values in South Florida. This market evidence may not, however,

be sufficient to persuade elected officials from mandating the allowance of pets in

common interest housing at the state level. As noted by Cannaday (1994), government or

condominium association regulations that result in uniform pet policies would eliminate

this amenity as a price determinant. Such interventions could result in social welfare

losses if some portion of condominium owners would pay more for units in pet restricted

condominium projects.

It would behoove those doing further research in the area of pet restrictions and

housing prices to repeat this process for other housing markets. Specifically, it would be

interesting to gauge residential demand for pets in various areas and to match those

findings with the consequences for housing prices.

18

References

Allen, M. (1997), “Measuring the Effects of ‘Adults-Only’ Age Restrictions on

Condominium Prices,” Journal of Real Estate Research 14: 3, 339-346.

Allen, M., J. Blascovich, J. Tomaka, and R. Kelsey (1991), “Presence of Human Friends

and Pet Dogs as Moderators of Autonomic Responses to Stress in Woman,” Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology 61(4).

Barker, S., and K. Dawson (1998), “The Effects of Animal-Assisted Therapy on Anxiety

Ratings of Hospitalized Psychiatric Patients,” Psychiatric Services, 49(6).

Cannaday, R. (1994), “Condominium Covenants: Cats, Yes; Dogs, No,” Journal of

Urban Economics 35, 71-82.

Carter C., Z. Lin, M. Allen, W. Haloupek (2011), “Another Look at Effects of ‘Adults-

Only’ Age Restrictions on Housing Prices” Journal of Real Estate Finance and

Economics (forthcoming).

Cheng, P., Z. Lin, and Y. Liu (2008), “A Model of Time-on-market and Real Estate Price

under Sequential Search with Recall,” Real Estate Economics 36, 813-843.

Duncan, S. (2000), “The Implications of Service Animals in Health Care Settings,”

American Journal of Infection Control, 28.

Endenburg, N., H. ‘t Hart and J. Bouw (1994), “Motives for Acquiring Companion

Animals,” Journal of Economic Psychology 15.

Ferrante, A. (2007), “The 2007-2008 APPA National Pet Owners Survey Data is

Launched at Global Pet Expo,” APPA Advisor, April.

Goodman, A. and T. Thibodeau (1997), “Age Related Heteroscedasticity in Hedonic

Housing Price Equations: An Extension,” Journal of Housing Research 8, 299-317.

Guntermann, K. and S. Moon (2002), “Age Restrictions and Housing Values,” Journal of

Real Estate Research 24:3, 263-278.

Guntermann, K. and G. Thomas (2004), “Loss of Age-Restricted Status and Property

Values: Youngtown, Arizona,” Journal of Real Estate Research 26, 255-275.

Hirschman, E. (1994), “Consumers and Their Animal Companions,” Journal of

Consumer Research 20.

American Pet Products Association (2008), Industry Statistics and Trends,

http://americanpetproducts.org.

19

Kennedy, P. (1984), “Estimation with Correctly Interpreted Dummy Variables in Semi-

logarithmic Equations,” American Economic Review 71, 801.

Lin, Z., Y. Liu, and V. Yao (2010), “Ownership Restrictions and Housing Value:

Evidence from Housing Market Survey,” Journal of Real Estate Research 32, 201-220.

Mallia, M. (2006), “The Role of Companion Animals in Senior Well-Being,”

unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Malpezzi, S. and D. Maclennan (2001), "The Long-Run Price Elasticity of Supply of

New Residential Construction in the U.S. and the U.K.," Journal of Housing Economics

10, 278-306.

Minnesota Real Estate Research Center (1990), Apartment Profiles Quarterly Review, St.

Cloud State University, 4

th

Quarter.

Moran, P (1950), “Notes on Continuous Stochastic Phenomena,” Biometrika, 37, 17–23.

Poliakoff, G. (2008). “You Have the Right to Emotional Support Animals in ‘No Pet’

Housing,” Condo Consultant, July.

Raina, P., D. Waltner-Toews, B. Bonnett, D. Woodward, and T. Abernathy (1999).

“Influence of Companion Animals on the Physical and Psychological Health of Older

People: An Analysis of a One-Year Longitudinal Study,” Journal of the American

Geriatric Society 47(3).

Schwarz, P., J. Troyer and J. Walker (2007), “Animal House: Economics of Pets and the

Household,” The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy 7(1).

Sirmans, G., C. Sirmans and J. Benjamin (1989), “Determining Apartment Rent: The

Value of Amenities, Services and External Factors,” Journal of Real Estate Research,

4(1).

So, H., R. Tse and S. Ganesan (1997), “Estimating the Influence of Transport on House

Prices: Evidence from Hong Kong,” Journal of Property Valuation and Investment, 15

(1), 40-47.